- Home

- Mary Jane Ryals

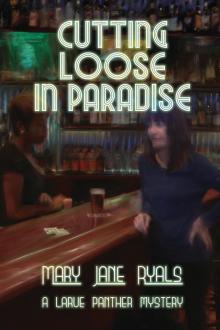

Cutting Loose in Paradise Page 9

Cutting Loose in Paradise Read online

Page 9

We were an eccentric mix, locals and implants, who had lived on the island awhile. We gossiped, but we cared. If someone had lost a job, people clustered to take them food for their pantries. When someone died, we gathered and prepared food. When someone was having an affair, somehow, most knew it. When someone had left someone, we often knew that, too. I was only hoping the same would happen to me, that people wouldn’t speculate about my wanting to kill Mac or Trina.

Gray clouds were rolling in thick and low, but no snow. I picked a table out on the glassed-in sun porch, sat in the most hidden spot and waited, huddled in a winter jacket.

Jackson entered the room looking rested. “Morning,” he said.

“Morning. Have a seat,” I said with awkwardness.

He opened his napkin and placed it in his lap. “Well, the lab results are back,” he said. “It was Percodan, and Mac is extremely allergic. The effects should have gotten to you, too, if you took a sip of his coffee.” He asked the waitress for coffee and asked if I wanted some. I nodded. He went on. “This matches not only your story, but also Mary’s and Mac’s.”

I shrugged. “I only had a small sip.” Laura came in and gave Jackson a tap on the head and me a shoulder hug. She sat down, and we all took off our coats.

“Small sip of what?” Laura said. “I hate winter.” Jackson ordered her coffee and briefed her on the lab findings.

“I did feel dizzy,” I said.

“Yes, but you’re allergic to Percodan, too, yet you didn’t show any slight reactions, like a rash, nausea.” I shrugged. I had a sneaking suspicion that Grandma Happy’s tea may have helped.

“Yikes!” Laura said. “By the way, Jackson, you’ll have to tell me if anything is off the record.”

“Like I don’t know that,” he said. “I worked for the Times, too, remember?”

Then he turned to me and said, “What’s odd is—” He turned back to Laura. “Off the record for now.” Then he turned back to me. “Your—tea. What was it? Could it have been an antidote for the poison?”

I gulped.

Laura looked at me strangely. Then at Jackson.

“Surely you don’t think LaRue—” Laura said.

“No, of course not. That’s off the record, too. But I have to take everything into account.” He turned to me. “But where did you get that tea? This is rather coincidental. The tea has Naloxone in it, which is the antidote for Oxycodone—or Percodan. Though it does make you feel dizzy.”

“Shit,” I said. I put my head in my hands.

“What is it, Rue?” Laura said.

“It was one of Grandma Happy’s concoctions,” I said. “I didn’t tell you, Jackson, because it was so—goofy.”

“Who’s this—Grandma Happy?” Jackson said.

Laura let out a short laugh and said, “LaRue’s eccentric grandmother. She’s Seminole, Native American, but she says that’s white people’s name for Indian. She’s always coming up with some folk herbal tea for LaRue. She thinks LaRue needs her help.”

“My grandmother didn’t do it,” I said. “She’s ninety-four. She couldn’t have, and please don’t bother her. My dad had a bypass a few years ago, and I don’t want him worrying about me.” The two of them watched me sit up erect.

The waitress brought coffee, and we got quiet, cupping chilly hands around mugs for a few minutes. I breathed deeply to fight anxiety. I could feel the slow watery pulse of our lives here. Breakfast-goers spoke softly, the tinkle of glass and slow steps of waiters enveloped us. I noted that the waitress was a Colton, a distant relative of the Lutzes. She handed us each a menu, went through the litany of specials and walked back inside. Jackson looked over the menu. Laura gave him suggestions on brunch. He had a frown crease on his forehead.

“LaRue, your dad will worry about you a lot less if I can keep you from being the lone, leading suspect,” Jackson said. “I’ll need to talk with your grandmother if she made the tea.”

I sighed. “She’s sort of intuitive. And sometimes she’s just short of weird. I don’t know which Happy you’ll get.”

“It’ll be interesting, at any rate,” he said.

“By the way, the waitress is a Colton,” I said quietly. “She’s a cousin of the Lutzes and she will spread rumors like warm butter spreads on toast. Please be careful.”

The rest of the time we enjoyed our meal. Jackson ate eggs Benedict with local shrimp. Laura watched us both as she ate an omelet. Her matchmaking skills were being put to the test, and she wanted to see how they were working. I pushed eggs around on my plate.

“Well, are you going to ask me questions or not?” I finally said. “About Trina Lutz?” We all glanced around. We were alone under a sun porch on a cloudy day.

“Sure,” he said. “I can do that.” He wiped his mouth, put down the cloth napkin and pulled out a small notepad and a pen. He said, “Laura tells me you saw something that the paper didn’t report about Trina Lutz’s suicide?”

“I didn’t tell him anything yet,” Laura offered. “I thought maybe you’d want to do the telling. I didn’t want to get anything wrong.” We waited as the waitress warmed up the coffee and left the check, which Jackson picked up.

As he put his credit card in the check holder, I told him exactly what I’d seen. And that unfortunately, I’d left that top button unbuttoned while the funeral home fellow had stood there. That I was finishing Trina’s hair, and the funeral home director wouldn’t go away. How even though the funeral was closed casket, Trina wanted to go below with good hair. Jackson jotted a few notes, losing all facial expression. I hoped that didn’t convey character but a part of the job.

“What’s the name of this funeral home fellow?”

I should have found out, I thought. I’m not so good at this. “I don’t know. Edwards and Parsons Funeral Home. Up on State Road Sixty-seven up in Wellborn.” He scribbled some notes.

“Can you describe this guy for me?” Jackson asked.

“Bad hair,” I said. Jackson looked up, waiting. “You know—slicked back and black. Straight,” I said. “Thick glasses, square and black. He looks like somebody, I just can’t place exactly who.”

“Well, do me a favor and try to place how you know him over the next few days, will you?” Jackson put away his notepad. Then a question came over his face. “Is he connected in any way to anyone who was at the reception last night?” Jackson said.

I shrugged. “Oh, for godsakes, I thought that might be your job,” I said in an uncharacteristic burst of frustration, my hands fluttering. “He could be related to anybody. That’s how it is around here, you know. A few big families, all scattered throughout the county. Everybody’s cousins with everybody when you go back generations.” I realized I was shouting. “Okay, I’ll try to find out,” I said, dropping my arms.

He held out a hand. “Take it easy, okay?” I took a deep sigh and glanced at Laura.

“Why don’t you relax this afternoon,” she said. “I’ll go check on the kids at Randy’s.” I thought a minute. Maybe things were happening between her and Randy.

“Well, I really want to see the kids.”

“They’re fine, LaRue. They’re better, really, not having your worrying. You’re keyed up. Why don’t you get some rest and then go see them tonight at Randy’s. Or maybe at my place,” she said, pulling a last sip off her coffee. “I’m going to run. Call if you need anything. See you, Jackson. Thanks for picking up the check.”

After she left, we got quiet, sipping coffee, watching as the fast-moving clouds flew across the sky, darker. Then the sun broke out.

“Uh. I have to ask you this,” Jackson said. “Did you put poison in Mac Duncan’s coffee to make him sick or to kill him?”

I looked at him square on. “No. I most certainly did not. It would only hurt my business to try to hurt Mac. He’s done a lot to bring customers to me. Don’t shut my business down. And don’t let out the news that I’m prime suspect just yet.”

“Please tell me you knew nothing abou

t what was in that tea your grandmother gave you.”

“No. I. did. not. I tried to turn the tea down when she handed it to me, but then I took it anyway. She’s stubborn. She said I was going to have a day of opposites and I needed it.” I felt funny confessing about Grandma Happy.

“A day of opposites?” he asked.

“A funeral and a wedding,” I said.

The Colton waitress came by again and took the bill holder. We waited until she left.

“How did she know?” he asked.

“My dad told her. And no, my dad did not poison Mac,” I said.

“When I took the tea out, it was to drown out the bitter flavor of that coffee. That’s all. The tea tasted sweet and sour. Very nice. Delicious, actually. I drank it all.” I picked up my glass of water, the sides now covered with condensation. I put it back down. “Are you helping me, or are you trying to put me in jail?”

He ignored the question. “That could explain why you had no real reaction to the Percodan,” he said. “Would you like to go somewhere more—less—you know, somewhere you’ll be comfortable talking?” he said, looking around.

I kept trying to remember that Laura asked him to help me, even though he was the law, sort of. A state investigator not officially on the case, whatever that meant.

I sighed. “Sure,” I said. The waitress brought back the receipt for him to sign. We were silent until she left. Then we stood and walked out to his car where the sun was shining.

“Where do you suggest we go?” Jackson said, putting his hands in his pockets, fishing for keys.

“My dad’s boat.” His eyes opened wide. “Don’t get excited,” I said, following him to his navy blue Toyota. “I’m not coming on to you. It’s a rowboat out on the pond at Panther Pit. I think you’ll like it. And if you must, you can question Happy and Dad. But you have to be gentle.”

“And if I’m not, you’ll all feed me to the pet alligator with an appetite for skunks?” he said, opening his door and using his unlock button to open the door on my side.

“That’s right,” I said, opening the passenger side door, grinning despite myself at the quick wit he seemed to have. Alligators and skunks, a combination to fear.

“Hey there,” said a melodic voice on the street as we sat down in the car. She pulled four syllables out of two. Madonna. Wearing a cashmere midriff top and low-slung jeans. Jackson got an eyeful, then turned to peer at me.

“How you doing?” she said, cocking her head and giving him an appraisal. Then she looked at me and grinned sideways like I’d just caught the big swordfish.

I squinted in the bright sun. “I’m the prime suspect in the poisoning.” I gave Jackson a dirty look. “He’s making it official.”

“Damn,” she said. “That sucks.” She looked at Jackson. “Well, I just wanted to tell you something about—well, something I heard. About Trina. Or the night Trina died.” She glanced around and stepped closer to lean in close to the passenger side window.

“Go on,” I said. She looked at him, then at me, and I nodded.

“Well, you know old OV?”

“OV Justus? Garbage man?” I asked.

“The very,” she said. “You know how he lives at the canal between the main key and Way Key? Well, he was tooling around in his little oyster boat, he’d been working on it, and he took it out for a little spin before sundown the night of the suicide. He says he swears he saw Trina on Fletch’s boat. You know the big yacht-looking thing?” She began to swing her arms and hips together. “I don’t know what they’re called, but it’s big and white?”

I nodded. “Inboard-outboard? Bigger than most?”

She leaned in, nodding. “Right when she was supposedly at home killing herself.”

“Yeah?” I said. “OV told you this when?”

“Last night when I went back to close up the bar. After the reception went kabloonk.”

“Can you get me his name, address, and phone number?” Jackson said.

I looked at Madonna, and she shrugged. “Confidential information. I’ll have to ask him if it’s okay.” Jackson shook his head, an amused smile across his face.

“I can question him anyway, but if you insist, you may ask him first.”

“Jackson, you got to understand people around here,” I said. “We all talk. We kind of trust each other. Kind of. And most folks don’t trust the law. At all. Fishermen and islanders are not into authority. Some of these folks think they’re freakin’ cowboys.” He nodded and then shook his head.

“Ms. . . . Madonna?” Jackson said. “Could you get the license number on that boat?” She nodded.

“Thanks, Madonna. I sure appreciate you. Every piece of information helps,” I said as Jackson started the car.

“Let’s go check out that boat tonight,” she said under her breath so Jackson couldn’t hear. I nodded and waved.

“I’ll call you,” I said.

CHAPTER 12

THE SUN WAS PLAYING shadow tag with our part of the world as Jackson and I drove through town. Over the first bridge, then the second of four. The weather would hold, no snow would fall. We headed away from the main island.

“Kiss-Me-Quick.” Jackson read the sign at the next island. “Now there’s an original.”

I launched into how the old railroad ran parallel to the current road. “And when the train came through, it slowed way down and the locals would jump on, head towards the mainland. You’d be with your sweetheart, and when you hear the train, you’d say—”

“Kiss me, quick!” He raised his eyebrows and opened his mouth clown-ishly. I pulled away from him, and he smiled. He had dimples and sprinkles of freckles.

“Where are you from anyway?” I said.

“My parents came from New York,” he said. “I grew up in Tallahassee.”

“The capital. I went to grad school there. A political kid? Your dad was—something, a right-wing lobbyist, one of those guys who wanted BP to drill, baby, drill in the Gulf?”

“No. I mean, I’m probably more liberal than anybody in the department, if that’s what you’re asking,” he said. “But to tell you the truth, LaRue, I just do what I think is right. That’s the only reason I left the Times. I felt I might better serve the underserved. Folks who get into trouble with the law and have no money to get a good lawyer.” God, he was killing me. We crossed the next two bridges.

“Where were the guys like you, the lawyers with ethics, when I was going through the divorce?” I pointed to the road, which split just ahead. “You want to turn right up there at the fork.”

“I’m not the bad guy, LaRue. How far from here?” he said.

“About six miles.” We passed big fat Phil, who had a box on a bike with a sign that said “Phil’s Knife Sharpener.” A Dixie flag hung in front of his box-bike.

“Hmm, nobody’s killed him yet,” Jackson said. “Dixie flags and knives somehow beg the question.” I had to laugh.

I hugged my legs as we rode through the low land of sabal palms mixed with sand oaks and tall pines. We passed trailers, the bikers’ property, old man Vickers’, and the Coltons’. The folks I’d grown up around. An old statue of a lion sat in front of the Colton entrance. Someone had painted the lion with a Mexican cape over a Santa suit to bring in the season.

“Quite a bit of this land is for sale,” he said. “Or just sold.”

I shrugged. “Most of the old timers are dying out. Families are trying to sell these rural properties off after they die. Trouble is, most of it would never pass the wetlands codes today. Couldn’t build on it.”

“Who’s buying it, do you know?” he asked.

“Hmm, not sure. Fletch Lutz has invested in some of it,” I said. “Trina’s husband. And Mac told me yesterday he was closing a deal out this way.”

“Fletch—Trina Lutz’s husband?” I affirmed that. “Anybody else?”

“I don’t really know,” I said. “Look, why don’t you let me off the hook? You don’t need to declare a leading suspect,

and you know I didn’t kill or poison anyone. I’ve got kids to support, and a lot of people won’t come see a leading murder suspect to get their hair cut.”

“Would you relax?” he said. “It’s okay. You won’t be under investigation for long, probably.”

We passed the Church of God in Holy Heaven set up in a trailer. A billboard out front stated, “It takes a lot of faith to be an Atheist.”

“Probably?” I let out a disgusted pffft. “Let me help out. I’ll help you investigate.”

He took his eyes off the road and studied me. Then laughed a little.

“It’s not funny,” I said.

“Okay. Okay, then. If I hadn’t noticed your haircuts, I probably wouldn’t agree to do this, you know. I have a weakness for good taste.” He combed my long body with his eyes.

I felt myself go red. I stared at the swamps on either side of the road. Low-country. Yellow winter grasses against blue sky.

He continued. “So, how many nurseries have businesses between here and Wellborn?”

“I’m not sure—one or two.” A sky wader, a blue heron stood like a nun, guarding her space up ahead on the road, working the shallows.

“And in Wellborn?” he said.

“I don’t know—maybe four, six nurseries at the most, if you count Wal-mart.”

“Find out where that palm came from,” Jackson suggested. On slow wings, a hawk was patrolling its possibilities.

“That’s not fair,” I said. “I could end up—”

“And find out, too, who’s buying up this property. That should be easy enough. Have Laura check the sales records in the County Courthouse.” This was trivial stuff. The hawk soared, slid down almost to ground level, radar eye to its prey that we couldn’t see.

“Can you think of anybody who didn’t like Trina?” he said. The swamps blurred as we sped on.

“Everybody liked and respected Trina. She was all over the oil spill thing. When BP came to the community meeting and Tallahassee came down with TV cameras, she stood up and raised hell in that meeting about how the fishermen who’d gone to work for BP had no health benefits. And how BP had made workers sign a waiver not to request liability coverage in case the workers had chemical or psychological damage while working for them.” We were passing the lower part of the river area, evidenced by the flocks of egrets flying overhead.

Cutting Loose in Paradise

Cutting Loose in Paradise